|

Bonn, Germany (SPX) Aug 24, 2010 An international research team led by David Champion, now at Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, with researchers from Australia, Germany, the U.S., U.K. and Canada, has come up with a new way to weigh the planets in our Solar System, using radio signals from pulsars. Data from a set of four pulsars have been used to weigh Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn with their moons and rings. The new measurement technique is sensitive to just 0.003% of the mass of the Earth, and one ten-millionth of Jupiter's mass (corresponding to a mass difference of two hundred thousand million million tons). The results are described in an article for the "Astrophysical Journal", which is publicly accessible via preprint-server. Until now, astronomers have weighed planets by measuring the orbits of their moons or of spacecraft flying past them. That's because mass creates gravity, and a planet's gravitational pull determines the orbit of anything that goes around it - both the size of the orbit and how long it takes to complete. The new method is based on corrections astronomers make to signals from pulsars, small spinning stars that deliver regular "blips" of radio waves. Measurements of planet masses made this new way could feed into data needed for future space missions. "This is first time anyone has weighed entire planetary systems-planets with their moons and rings," says team leader Dr. David Champion of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy. "In addition, we can provide an independent check on previous results, which is great for planetary science." The Earth is travelling around the Sun, and this movement affects exactly when pulsar signals arrive here. To remove this effect, astronomers calculate when the pulses would have arrived at the Solar System's center of mass, or barycenter, the rotation center for all the planets. Because the arrangement of the planets around the Sun changes with time, the barycenter moves around too (relative to the sun). To work out its position, astronomers use both a table with the positions of the planets in the sky (called an ephemeris), and the values for their masses that have already been measured. If these figures are slightly wrong, and the position of the barycenter is slightly wrong, then a regular, repeating pattern of timing errors appears in the pulsar data. "For instance, if the mass of Jupiter and its moons is wrong, we see a pattern of timing errors that repeats over 12 years, the time Jupiter takes to orbit the Sun," says Dr. Dick Manchester of CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science. But if the mass of Jupiter and its moons is corrected, the timing errors disappear. This is the feedback process that the astronomers have used to determine the planets' masses. Data from a set of four pulsars have been used to weigh Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn with their moons and rings. Most of these data were recorded by CSIRO's Parkes radio telescope in eastern Australia, with data contributed by the Effelsberg telescope in Germany and the Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico. The masses were consistent with those measured by spacecraft. The mass of the Jovian system (Jupiter and its moons), 0.0009547921(2) times the mass of the Sun, is significantly more accurate than the mass determined from the Pioneer and Voyager spacecraft, and consistent with, but less accurate than, the value from the Galileo spacecraft. The new measurement technique is sensitive to a mass difference of two hundred thousand million million tons - just 0.003% of the mass of the Earth, and one ten-millionth of Jupiter's mass. In the short term, spacecraft will continue to make the most accurate measurements for individual planets, but the pulsar technique will be the best for planets not being visited by spacecraft, and for measuring the combined masses of planets and their moons. Repeating the measurements would improve the values even more. If astronomers observed a set of 20 pulsars over seven years they'd weigh Jupiter more accurately than spacecraft have. Doing the same for Saturn would take 13 years. "Astronomers need this accurate timing because they're using pulsars to hunt for gravitational waves predicted by Einstein's general theory of relativity", says Prof. Michael Kramer, head of the "Fundamental Physics in Radio Astronomy" research group at Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy. "Finding these waves depends on spotting minute changes in the timing of pulsar signals, and so all other sources of timing error must be accounted for, including the traces of solar system planets."

Share This Article With Planet Earth

Related Links Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy The million outer planets of a star called Sol

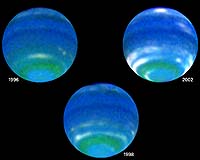

Pounding Particles To Create Neptune's Water In The Lab

Pounding Particles To Create Neptune's Water In The LabWashington DC (SPX) Jul 23, 2010 We know 'icy' Neptune is partially comprised of water molecules but until now we have had little means to test how water behaves in the extreme conditions that Neptune presents. This is about to change as an international group of physicists draw up plans to use the new Facility for Antiprotons and Ion Research (FAIR) in Germany, which will be ready in 2015, to expose water molecules to he ... read more |

|

| The content herein, unless otherwise known to be public domain, are Copyright 1995-2010 - SpaceDaily. AFP and UPI Wire Stories are copyright Agence France-Presse and United Press International. ESA Portal Reports are copyright European Space Agency. All NASA sourced material is public domain. Additional copyrights may apply in whole or part to other bona fide parties. Advertising does not imply endorsement,agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided by SpaceDaily on any Web page published or hosted by SpaceDaily. Privacy Statement |