|

Pittsburgh PA (SPX) Mar 30, 2011 There are billions of neurons in the brain and at any given time tens of thousands of these neurons might be trying to send signals to one another. Much like a person trying to be heard by his friend across a crowded room, neurons must figure out the best way to get their message heard above the din. Researchers from the Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition, a joint program between Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh, have found two ways that neurons accomplish this, establishing a fundamental mechanism by which neurons communicate. The findings have been published in an online early edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). "Neurons face a universal communications conundrum. They can speak together and be heard far and wide, or they can speak individually and say more. Both are important. We wanted to find out how neurons choose between these strategies," said Nathan Urban, the Dr. Frederick A. Schwertz Distinguish Professor of Life Sciences and head of the Department of Biological Sciences at CMU. Neurons communicate by sending out electrical impulses called action potentials or "spikes." These spikes code information much like a version of Morse code with only dots and no dashes. Groups of neurons can choose to communicate information in one of two ways: by spiking simultaneously or by spiking separately. To find out how the brain decided which method to use to process a sensory input, the researchers looked at mitral cell neurons in the brain's olfactory bulb - the part of the brain that sorts out smells and a common model for studying global information processing. Using slice electrophysiology and computer simulations, the researchers found that the brain had a clever strategy for ensuring that the neurons' message was being heard. Over the short time scale of a few milliseconds, the brain engaged its inhibitory circuitry to make the neurons fire in synchrony. This simultaneous, correlated firing creates a loud, but simple, signal. The effect was much like a crowd at a sporting event chanting, "Let's go team!" Over short time intervals, individual neurons produced the same short message, increasing the effectiveness with which activity was transmitted to other brain areas. The researchers say that in both human and neuronal communication alike, this collective communication works well for simple messages, but not for longer or more complex messages that contain more intricate information. The neurons studied used longer timescales (around one second) to convey these more complex concepts. Over longer time intervals, the inhibitory circuitry generated a form of competition between neurons, so that the more strongly activated neurons silenced the activity of weakly activated neurons, enhancing the differences in their firing rates and making their activity less correlated. Each neuron was able to communicate a different piece of information about the stimulus without being drowned out by the chatter of competing neurons. It would be like being in a group where each person spoke in turn. The room would be much quieter than a sports arena and the immediate audience would be able to listen and learn much more complex information. Researchers believe that the findings can be applied beyond the olfactory system to other neural systems, and perhaps even be used in other biological systems. "Across biology, from genetics to ecology, systems must simultaneously complete multiple functions. The solution we found in neuroscience can be applied to other systems to try to understand how they manage competing demands," Urban said. Co-authors of the study include Brent Doiron, assistant professor of mathematics at the University of Pittsburgh, and Sonya Giridhar, a doctoral student in the Center for Neuroscience at Pitt. Both are members of the Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition.

Share This Article With Planet Earth

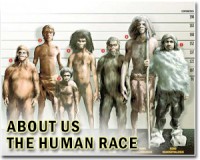

Related Links CMU's research in brain, mind and learning All About Human Beings and How We Got To Be Here

Rare gene defect affects both pain, smell

Rare gene defect affects both pain, smellLondon (UPI) Mar 23, 2011 People with a rare genetic defect who are unable to feel pain also are unable to smell anything, as the same nerve protein is involved, U.S. researchers say. The discovery shows nerves that detect pain and those that detect odors rely on the same protein to transmit information to the brain, ScienceNews.org reported Wednesday. An international team of researchers examined three p ... read more |

|

| The content herein, unless otherwise known to be public domain, are Copyright 1995-2010 - SpaceDaily. AFP and UPI Wire Stories are copyright Agence France-Presse and United Press International. ESA Portal Reports are copyright European Space Agency. All NASA sourced material is public domain. Additional copyrights may apply in whole or part to other bona fide parties. Advertising does not imply endorsement,agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided by SpaceDaily on any Web page published or hosted by SpaceDaily. Privacy Statement |